Prologue

Carter Ratcliff

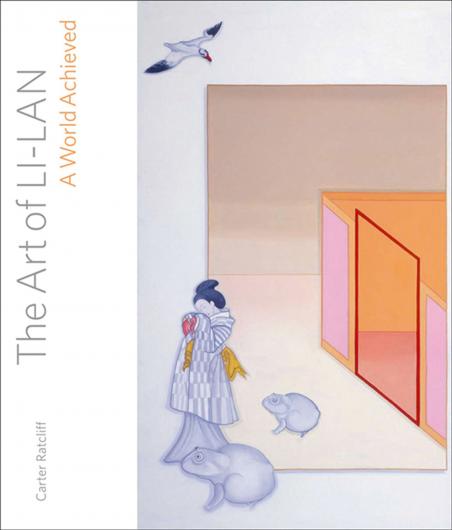

The Art of Li-lan: A World Achieved

2013

Li-lan is an artist with a complex heritage. Her mother, born Helen Wimmer, was an American of German descent. Yun Gee, her father, was born in a village in Guangdong Province, an immense territory that stretches along the southern coast of China. Immigrating to San Francisco in 1921, at the age of fifteen, he studied painting at the California School of Fine Arts. By the end of the decade, Yun Gee had settled in Paris and found an audience for his distinctive variants on modernist styles-Cubism, chiefly, though there are traces of Fauvism and Futurism in his early work. He left Paris for New York in 1930.

When Yun Gee met Helen Wimmer, in 1935, she was a young art student and he was an avant-garde artist with an exhibition record. Several Manhattan galleries had exhibited his work, and he was included in group shows at the Museum of Modern Art and the Brooklyn Museum. Helen and Yun Gee were drawn to one another, and yet he returned to Paris soon after they met. The pervasive racism of American society had become unbearable.

In 1939, as war threatened Europe, Yun Gee returned to New York. Married in 1942, he and Helen lived in a top-floor studio on East Tenth Street, between Broadway and University Place. Li-lan was born the following year. Two years later, her parents separated. Helen took Li-lan to live with her sister, Ellen, in an apartment on West 14th Street. Eventually, Li-lan’s parents were divorced. Though Yun Gee had some success in the New York art world of the 1940s, his career slowly faded. To support herself and her young daughter, Helen found various jobs, including painting roses on porcelain boxes. In the morning, she would deliver Li-lan to nursery school, leaving her there until six in the afternoon. Li-lan has a memory of watching her in the evenings, as she painted porcelain lids she had brought home from the factory. Later, she trained herself in the craft of photographic retouching and found work in that field.

After her parents’ separation, Li-lan spent weekends with Yun Gee, who still lived in the Tenth Street studio. He would cook Chinese food, which she loved, and they would play chess. As he painted, so would she and sometimes he gave her exercises to do. Yun Gee tried to teach his daughter to speak Chinese, without much success. As the only Asian-American child in her school, she shied away from anything that would mark her as different from others. Despite his daughter’s resistance to his native language, her father was kind and encouraging. Li-lan enjoyed her weekend visits. Yun Gee’s studio was filled with paintings, his own and others he acquired at antique shops and flea markets. There were birds in cages and shelves filled with books in various languages. Yet it troubled her that he drank-white wine, usually-throughout the day. Constantly making plans for advancing his career, he maintained a show of optimism. He kept up with friends. Nonetheless, he seemed isolated, even lost.

In 1954, Helen Wimmer, her sister, and her brother-in-law Charlie Berland opened the Limelight, a café and photography gallery on Seventh Avenue South, in Greenwich Village. Though Helen showed work by leading photographers-Alfred Stieglitz, Berenice Abbott, Robert Frank, Brassaï, Gordon Parks, Minor White-she just barely managed to keep the establishment afloat. The difficulty, in part, was that she could never obtain a liquor license. The Limelight had to subsist as a coffee house with a sideline in photography. In those years, the New York art world was just beginning to coalesce. Contemporary painting had few collectors and even fewer focused on serious photography. Sales at the Limelight were rare.

Li-lan liked to spend time at the café, chatting with the waitresses and helping, occasionally, with the installation of an exhibition. She enjoyed meeting the photographers and took a lively interest in their work. Carefully budgeting her allowance, she managed to buy prints by Minor White and several others. Her earliest ambition was to be not a photographer or a painter but an actress. When she was thirteen years old, she wrote plays, which she and her friends performed in her apartment, for paying audiences. In 1956, she entered Manhattan’s High School for Performing Arts. School days were divided between academic subjects and dramatic subjects-acting, improvisation, voice and diction, play writing. Li-lan and her friends often did their homework in the Sculpture Garden of the Museum of Modern Art. Occasionally, they visited the museum’s galleries. Though Li-lan was a good student, she slowly lost interest in the theater. By the time she graduated from high school, she knew that her career would not provide her with the company of others, in the collaborative art of the stage. She would work alone, in a painter’s studio. This, she realized, is what her temperament demanded, yet it was not an entirely happy realization. Li-lan understood early that to become a painter is to risk isolation.

In previous centuries, artists employed assistants. A successful studio was a crowded workshop. Li-lan follows a more recent model, which makes the painter responsible for every step in the process of completing a work. Until she switched to linen, in 1991, she stretched and primed her own canvases. To make a painting, she must be alone with it, often for months. Once it is finished, she offers it to an audience largely unknown to her. Ideally, Li-lan’s images draw the viewer into a solitude comparable to the one that engulfed her as she worked. In this scenario, solitude enables creativity-first the artist’s and then the viewer’s, whose response will be, at best, a work of the imagination.

Withindoors, 2006

There is no one right way to understand Li-lan’s art. It is up to each of us to find interpretations that feel satisfactory. So my readings are my responsibility. Face to face with a painting by Li-lan, I am alone with it, but not isolated. From within my point of view, I engage hers. It is tempting to suppose that art overcomes individual differences. In truth, it does the opposite. The richer my interpretation of Li-lan’s art, the stronger is my sense of myself as an interpreter, as one sensibility communicating with another. Again, this communication does not depend on a correct reading of Li-lan’s art. It depends, rather, on my willingness to be open to the extraordinary potential of Li-lan’s imagery. Her paintings are rife with discoverable meaning, and the discovery-or the invention-of that meaning is what brings us together in the space we share with one another and everyone else who responds to her art. This is the space of civilization. Embracing solitude, Li-lan became a distinctive presence in this shared space. She became herself, the author of a major oeuvre.

Carter Ratcliff is a leading art critic and contributing editor of Art in America. He has received numerous awards of distinction for his work, including the College Art Association’s 1987 Frank Jewett Mather Award for Art Criticism, a Guggenheim Fellowship, two national Endowment for the Arts’ Art Critics Grants, and a Poets Foundation Grant. His writings have appeared in American and European journals and in the publications of museums including the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the Guggenheim in New York, and the Royal Academy in London. He has taught at the School of Visual Arts and Hunter College and has lectured at a variety of institutions, including the Whitney Museum of American Art and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. He is the author of a collection of essays, The Figure of the Artist (2000, Cambridge University Press), and The Fate of a Gesture: Jackson Pollock and Postwar American Art. He lives in New York City.

The Art of Li-lan: A World Achieved is now available: