Li-lan

Tatsuo Oshima

Li-lan – Nantenshi Gallery Exhibition brochure, Tokyo

November 1971

Between Monday Morning and Saturday Night – 1971

Between Monday Morning and Saturday Night – 1971

Li-lan paints. She paints a cosmos of forms and colors. Time is transmuted to space on her canvas.

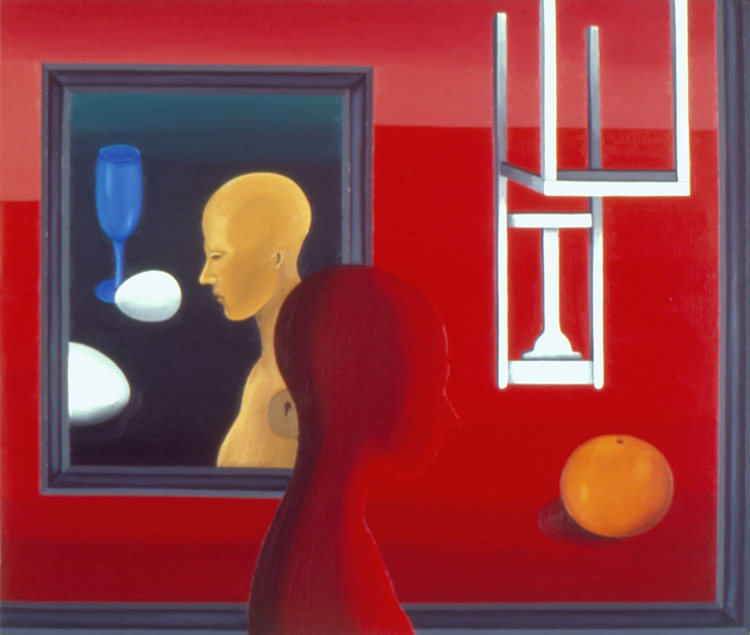

Various hues of blue – cobalt, indigo, and the colors of the sea and the sky – open a space far from the other. These spaces compose a picture within the picture, framing various images as if they are reflected in a many-sided mirror or a multi-screen. It is a drama. In her world, spaces multiply themselves to make time. There is a window n the space, which is a passage for time. Space is divided, layer by layer into the depths of the picture. The division of the screen is, in her case, rather an articulation of time than a segmentation of space. It is a poetic refrain or a musical sound of life. It is love, just like a hyphen uniting time and space.

Silhouettes both still and in motion; a picture within a picture, a space far apart from the other; windows, doors, chairs, and the slender shapes of trees; eggs, apples, oranges, and glasses… These objects, in a sense, live renewed in her from that flowering time of the Renaissance; they are the proofs of her day-to-day life. Her pictures are a passport to her “life.” In other words, they are staves in which those objects are placed to serve as notes. There, we can find the same naivety, charm, tenderness, and purity as in the frescos of Giotto. In her world, the afterimages of the Renaissance, silhouettes and profiles, retain the serenity of Piero della Francesca and also the dynamism of Uccello.

Li-lan’s apples wear the crimson of the Renaissance, but her chairs are nothing but Li-lan’s. They are not at all the same as van Gogh’s wooden chair or “le Siege de l’air of Arp. Her egg is a cloud of pale white drifting in the sky within her inner self. If a shade can be felt in her fresco-like or relief-like world, that shade itself may be evidence that she lives here and now. The objects of her everyday life cherish a loneliness of existence. It is not, however, a centrifugal alienation, but a centripetal isolation. In this sense we can call her an “intimist” of our time.